I’m going to talk about my summer project tonight. In a previous post I shared an extract from Kathe Kollwitz diary, which showed her reaction to her dismissal from the Prussian Academy. In the extract Kollwitz discussed the “silence” that came down around her. She seemed dismayed that nobody talked to her. She became an outcast. Though it could be argued that she was outcast from society all her life because of her sex and her views.

However, within the artistic community of the time Kollwitz was not alone in her views. In the elections that were held before 1933 there was growth in support for both the socialists and the communists. The SPD ( the socialist party in Germany ) had been the majority party in the many coalition governments since 1918. But the SPD influence and success was limited from day one. The Left wing parties split early on in the Republic (SPD and KPD) over many issues, on of the main ones being the Ebert – Groener Pact and the continuing existence of the old elite including army Generals such as Ludendorff and Von Hindenburg. General Von Hindenburg would go on to become President and give Hitler the Chancellorship in 1933. The German revolution was as much a revolution from above as it was from below. The old elite had dreams of reinstating the monarchy and as the saw it making Germany great again. However Kollwitz and many others like herself had been snubbed by the old elite because of their socialist views. On of Kollwitz’s greatest and earliest, the series The Weaver’s Uprising was not well received by the elite or the Kaiser. He refused for Kollwitz to be awarded a gold medal for her work. She would later achieve recognition for this work as within the artistic community it was praised. The weaver’s series was greatly liked by Adolf Menzel a prominent German artist of the time. It was he who put her forward for the gold medal. The Weaver’s Uprising consisted of six images; poverty, Death, Conspiracy, Weavers on the march, Attack and the End. In my opinion it was probably a pretty accurate portrayal of life for farming communities. Problems with agriculture and farming continued into and beyond world war one. Even before the hyperinflation of 1923/24 farmers were struggling and calling out for land reforms. The reforms didn’t happen and any that did had little effect.

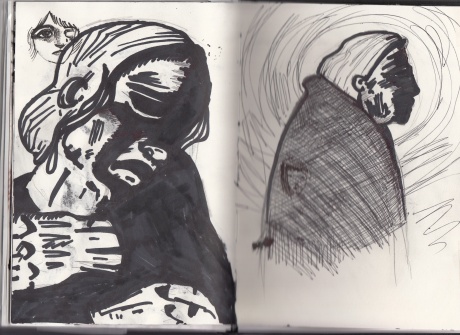

Kollwitz was deeply affected by the war and the death of her son, Peter in 1914. At the end of the war she wrote: “Peter and millions, many millions of other boys, all betrayed.” Germany had lost the war, many were starving and sick. The country had been led to believe they were winning or had a chance if winning right up until the end. They felt cheated and betrayed. And for what, a dead Arch duke from a different country and a couple of dreadnoughts? Of course that is a very simple take on a few of the many reasons for the beginning of WW1. Kollwitz was not alone in her grief over the death of her son, she saw the war-torn families that came into her husbands surgery. Kathe Kollwitz expressed herself through her work ( German expressionists fancy that they expressed themselves ). But more than that she was able to empathise with the everyday man or woman on the street, she could capture their anguish and their troubles because they were her troubles to. I feel she was a very down to earth person, who really believed in her views and carried through with them to the best of her ability. She is a voice for the forgotten millions of inter war Germany. When everybody else thinks of Art Deco and the rise of Hitler. Others will remember the people of Germany and their survival and the artists who painted them who over shadowed by a regime.

Many people were forced out of their jobs once the Nazis came into power, it began with the Jews and supporters of the Left. But like Kollwitz wondered what did her colleagues make of her dismissal?, what did the man on the street think of the SA smashing his Jewish grocers windows? It’s hard to know for sure what the general populace thought of these actions. Historians such as Ian Kershaw and Saul Friedlander have discussed this topic at length in their respective books on the Nazi’s anti – Semitic policies. To break it down people fell into the categories of indifferent, supportive and resistant towards such policies. Many people simply wanted to survive, whether that meant supporting or opposing Nazi policies. When the Nazi’s did an early boycott of Jewish owned businesses, many Germans found it most baffling, they just wanted to do their shopping and say hello the shopkeeper they had been going to for years. Many helped clean up the glass from the smashed windows. This was early days of course and I do not wish to discuss what lies down that road tonight. This is a very complex series of events in history. I think it is one of the most interesting periods but at the same time one of the most traumatic. In historical terms, these events are still very fresh and recent. Books by the likes of Kershaw and Friedlander on the opinions of the average German 1918 – 1945 are relatively new. I highly recommend their books, as they give an insight into the many different facets of Germany and German life from 1933 to 1945.

Here is a link to the Spartacus history website which has an extensive page on Kathe Kollwitz : http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/ARTkollwitz.htm (SIMKIN, J. Kathe Kollwitz. accessed 7.10.2013.)